Three-Time World Karate Champion Elisa Au America’s First Female World Karate Federation Champion

A world champion in karate, Elisa Au was born and raised in Honolulu. She began karate training at the age of five under the guidance of master Chuzo Kotaka. Now with over three decades of experience under her belt, she has achieved numerous pioneering firsts and secured many medals, such as her title as a three-time World Karate Champion. She is the Chair of the USA National Karate-do Federation, President of the World Karate Federation’s National Federation of the United States, a passionate entrepreneur and a mother of two. Tokyo Journal Editor-in-Chief Anthony Al-Jamie sat down with Elisa Au to learn more about her achievement as the first American woman to win a World Karate Federation championship and to talk about the latest developments in karate, her journey into the sport, what she loves most about karate and her involvement with the Guardian girls Initiative.

TJ: What island are you from?

AU: Oahu. Fun fact: [Karate Olympian] Sakura Kokumai is from the same dojo as me, as is the other world champion, George Kotaka. It is his father’s dojo. More World Championship medals from Americans came from my dojo in Hawaii.

TJ: Is karate big in Hawaii?

AU: Yes, martial arts in general are popular. There’s a strong Asian influence like in Southern California. I would say maybe even more so because it’s very isolated. Martial arts is huge on the islands.

TJ: How did you get started?

AU: I don’t remember vividly, but the story my mom tells me is that I came home from school one day with a flyer for karate lessons at the YMCA across the street from my house. She told me I was really excited about it and that I wanted to give it a try. So, she just walked me across the street, and we signed up. No one in my family had ever done martial arts before. It was just something I had wanted to do at age five in kindergarten, and I never looked back.

TJ: Why have you dedicated so much of your life to karate?

AU: I just love it. My position as the chair is a volunteer position. I’m not a paid board member. Karate has fundamentally changed my life from the moment I started at age five at the YMCA. It changed everything about my dreams and aspirations. I won my first World Championship when I was 21, and that just molded me for life. I feel like I owe a great deal back to the sport.

TJ: Can you describe what is happening in the world of karate these days?

AU: In the karate world, a lot of good things are happening. We have the World Championships every year. We alternate between the juniors and the seniors but starting next year we’re going to have a World Championship for teams. We’ve had the Premier League events, and those are equivalent to the Grand Prix or World Cups of other sports. Those happen four times a year. The exciting thing is having the kids as a part of this because they’re our future, so we have youth league events. We have five of them a year, and some of them have as many as 3,000 kids who compete.

TJ: Is the popularity of karate growing?

AU: I would say it continues to grow. We looked up a lot of stats in the past year and our YouTube channel is number four out of all sports, not just in Olympic sports but out of any sport. If you categorize them, we have the fourth busiest YouTube channel.

TJ: Have you ever used your karate in a street fight?

AU: I am very lucky that I never had to do that, but I do say this a lot when I teach self-defense classes: It’s all about confidence. It’s not an ultimate shield. Karate has helped me become a confident person, but as far as actually needing to use the skills outside the dojo, no, I haven’t.

TJ: Can you tell me about your involve- ment with the Guardian Girls initiative? Is it hard training people when it’s their first day?

AU: I’ve been a teacher for so long and my dojo is all about helping those below you. As young as eight years old, I was helping and assisting, so I’m used to it. I enjoy it a lot. I enjoy teaching beginners, and I enjoy teach- ing high-level elite athletes.

Sakura Kokumai From the Karate Dojo to the Tokyo Olympics

Sakura Kokumai is an American karateka [karate practioner] in the kata discipline. At the time of the sport’s debut in the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, she was ranked fifth in the world. Kokumai started practicing karate at the age of 7 in a small after-school program sponsored by the YMCA. She soon rose to national prominence. At the age of 14, Kokumai was picked for the U.S. Junior National Team. She has recently been taking part in the Guardian Girls self-defense initiative in L.A with World Karate Champion Elisa Au. She has not lost her place since on the U.S. Senior National Team. Tokyo Journal Editor-in-Chief Anthony Al-Jamie sat down with Sakura Kokumai for an interview about her long-lasting success and how she kept this up during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as how she prepared for and competed in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

TJ: How did you get started in karate?

SAKURA: I started when I was seven at a YMCA after-school program and did sports like any other young kid. I did everything, but I ended up sticking with karate because it’s something that I enjoyed doing, and I just continued. From the YMCA, I moved to IKF [International Karate Federation]. I was training under [Chuzo] Kotaka sensei.

TJ: I understand you studied in Japan. How long did you study there?

SAKURA: I moved from Hawaii to go to school in Japan. I went to university for a total of six years at Doshisha University in Kyoto and Waseda University for my master’s degree, plus working in corporate for one year. Throughout that entire time, I was practicing karate there. It was definitely hard because I had to juggle school and karate, but I managed to do both. I studied under [Yoshimi] Inoue sensei as well when I moved to Hotori in Japan.

TJ: Who do you study under now?

SAKURA: Inoue sensei passed six or seven years ago. Since then, I’ve been very fortunate to be training under different senseis in Japan. I train with Rika Usami. [In Southern California], I also train in my garage by myself. When you always compete, as much as you need to rely on yourself, you do need feedback and criticism. As I compete, travel and train, I do rely on other people to give me advice and criticism.

TJ: What are some of the major differences between karate in the U.S. and learning karate in Japan?

SAKURA: Definitely the culture. In Japan, it’s part of the curriculum; so, from grade, middle and high school, a lot of the Japanese kids learn the discipline that comes from the sport. It’s what basketball and football are to the U.S. In comparison, I see how challenging it is to stay because karate isn’t considered a sport in North America. A lot of kids go through high school and college, and they end up choosing their life sometimes over karate. Athletes from both countries are just as dedicated and focused. The environment is very different.

TJ: What was it like to compete in the Olympics?

SAKURA: They were saying they were going to cancel it, so the fact that it actually happened was a blessing and everybody was just happy to be there. We were all there to celebrate the Olympic Games happening. When they first announced that they were going to postpone it, it was a hard pill to swallow because we weren’t sure what was going to happen.

TJ: Can you tell us about the April 2021 anti-Asian attack you experienced in Orange County, California?

SAKURA: I was in the park very close to where I was staying and a stranger was yelling racial slurs at me. He never got close enough where I could have been physically hurt. I posted it [on Instagram] for myself because I needed to process it. That’s when I realized the power of social media. It exploded and all the news outlets picked it up, including overseas. It was, and still is, an issue that is happening around the world.

TJ: What’s the most important thing about being a martial artist?

SAKURA: For me, being able to practice karate and martial arts. It’s a lifelong sport. Right now, I’m still competing. But when I retire, I’ll still continue to practice karate. It’s a lifelong journey of developing and working on yourself and how much you can inspire others. It separates us from other sports. The culture that comes with it, the respect, the discipline. When you go to a dojo, it’s a family. You build this personal connection with these people because it’s a spiritual journey.

Olympic Gold Medalist Ryo Kiyuna Calmness and Gratitude

Training from a young age, Ryo Kiyuna has made his Okinawan craft known worldwide by becoming a champion karateka, or karate practitioner. With a mindset of refinement and by honing his inner strength, he has won four gold medals in the men’s kata – a system of individual training exercises for practitioners of karate and other martial arts – event at the World Karate Championships and two gold medals in the Men’s Kata event. Kiyuna embodies the true karateka, and just like his masters before him, he wants to hone and encourage the next generation of karatekas to pursue their love of the sport. After spending more than half of his life in the limelight, the 32-year-old Okinawa native left his final mark on the karate world at one of the most prestigious sports events — the 2020 Tokyo Olympics — by winning the gold medal in kata. As an adored karate icon throughout Japan, he is leaving his legacy as one of the greatest karatekas who have graced the karate world. Now working with his sensei, Tsuguo Sakumoto, he instills virtue and confidence in his students in Okinawa. Tokyo Journal Editor-in- Chief Anthony Al-Jamie spoke with Kiyuna about his training routine, his emotions while becoming an Olympian and what his next plans are.

TJ: Who was your karate master, and how long did you study under him?

KIYUNA: [I studied under] Master Tsuguo Sakumoto. His sensei was Nakaima sensei, who founded Ryuei-ryu [Ryuei-ryu Okinawan karate]. I have studied under Sakumoto sensei since I was 15 years old, and I still train every day with him. Sakumoto sensei and I currently teach together every day at my dojo in Okinawa.

TJ: What is your dojo’s name, and why is it so special?

KIYUNA: The name of my dojo [a place for immersive and experiential learning and meditation] is Ryuei Ryu Kiyuna Ryuhou Kan. It is in Okinawa City. I think everything about karate is wonderful, not just the Ryuei-ryu karate. Ryuei-ryu is characterized by the fast speed of techniques and because of the zig-zag movements in kata, which is called tai sabaki (body management). There is also a technique where offensive and defensive movements are conducted together at the same time.

TJ: Do you have a martial arts hero? Or someone you look up to?

KIYUNA: Since middle school, I have admired Sakumoto sensei’s katas. I have been pursuing them as my ultimate goal. My senpais (seniors at work or school) are also my heroes. I have looked up to my senpais, too, who are world champions.

TJ: What kind of training do you do every day? Are push-ups or weight training better for karate?

KIYUNA: I do kata training every day, but I do weight training as well. Both push-ups and weight training are good, but it might be dangerous to use weights if you cannot support the weight of your own body in your push-ups. So, I’d start with the weight of my body and then add weight gradually.

TJ: How about your diet — what do you eat? Do you eat junk food like McDonalds?

KIYUNA: I do not, usually (laughs). Sometimes I do. But I’d eat anything! I eat a lot of fish, meat and potatoes – as much as a sumo wrestler.

TJ: How did you feel about participating in the Olympics?

KIYUNA: I felt nervous, but I also enjoyed it. However, I was able to control my feelings because I train every day and I have confidence in myself. I also felt that I was not alone. I received encouragement and support from many people, so during the competitions on the Olympic court I felt strong and that I was fighting together with everyone. I was able to participate with calmness and gratitude.

TJ: Is training for the Olympics different from training for karate itself?

KIYUNA: I still train with the mindset that I am competing, and also with the intention to completely master karate by continuously refining my techniques.

TJ: What do you think the Olympics’ effects were on karate?

KIYUNA: I think the Olympics helped more people to know about karate. Watching the Olympics, I felt that the level of techniques in countries across the world has increased as well. I think that the Olympics is the dream or goal for many people. A lot of children are also thinking that they want to participate in the Olympics in the future, so I think the games created big dreams for children.

TJ: What will you do now that you’re running your dojo in Okinawa?

KIYUNA: I am already retired from competitions, so I want to train my students at the dojo to become world champions. That is my goal. But I also want to create opportunities for children to have dreams and hopes through karate.

TJ: Do you have any advice outside of fighting?

KIYUNA: I think it’s to live with confidence in yourself. Although this might be difficult, I think that by doing karate, if both your body and mind become stronger through training, you will be more confident.

Karate Master Tomohiro Arashiro Helping to Introduce Karate to the United States

As an ambassador of Ryuei-ryu, Tomohiro Arashiro has helped build this style of karate from a family practice in Okinawa to a style practiced around the world. He started training at the age of 15 and majored in physical education at Chukyo University in Japan. Arashiro went on to train with his sensei at a dojo in Okinawa before moving to the United States to teach Ryuei-ryu, helping to make it a well-known style. Arashiro eventually became the Pan-American Chief Instructor for the Okinawa Ryuei Ryu Karate Kobudo Organization (ORRKKO) and one of the 36 founding members of the Japanese Karate Masters Association of North America. Arashiro still returns to Okinawa to train with Karate Master Tsuguo Sakumoto. Tokyo Journal Editor-in-Chief Anthony Al-Jamie asked Tomohiro Arashiro to talk about his journey with karate and his advice to the karate world.

TJ: How did you get started in karate?

ARASHIRO: I had a childhood friend. He wanted to train in karate, but we lived in the countryside in Nago city and it took about 30 minutes to go to the nearest dojo. So, his father said, “Your principal is a karate master, Kenko Nakaima. If you want, I can ask the principal. But you must pick one of your friends. Karate is hard work, so if you bring a friend, you can help each other.” So, that was me.

TJ: And how old were you?

ARASHIRO: Fourteen or 15. The principal had a house in the school area. He had a small yard to train outside. We had a lot of rain, depending on the season. So, when it rained we went to the school classroom.

TJ: How long did you study under him?

ARASHIRO: During junior high school and three years of high school. Then I went to college in Japan. During vacation time, we would go back and train with him again.

TJ: Where did you study?

ARASHIRO: At Chukyo University. I majored in physical education. They had a Wado-ryu karate club, and I studied Wado- ryu for four years. I think I graduated in ’77. Sakumoto sensei had a dojo at the community center, so I helped his dojo twice a week. After we finished class, we would go to the bar across the street. One day, we were just drinking, and he said, “Hey, what do you think about going overseas and opening our Ryuei-ryu?”

TJ: What year did you come here?

ARASHIRO: 1979.

TJ: What is the difference between com- petitive and traditional karate?

ARASHIRO: In traditional karate, long ago, they fought and maybe killed each other. But now competitive karate has rules. In traditional karate, you train not just to compete with other people but with yourself. In competitive karate, it’s just like other sports. If you win, you’re happy. If you lose, you’re not happy. Of course, you don’t like losing, but you must bow and show respect even if you lose. But some competitors don’t do that anymore.

TJ: What is the best way to avoid fighting?

ARASHIRO: The best thing is to avoid dan- gerous places, like bars or not-so-safe areas at night without much light. Sometimes people are just looking for a fight, which can be very dangerous.

Grandmaster Minobu Miki The First Person Outside Japan to be Awarded the 8th-Degree Black Belt

Since the 1972 opening of the Japan Karate-Do Organization dojo in San Diego, Minobu Miki has established himself as a world-renowned Karate-do instructor. From his childhood, he grew up a dedicated student of Japanese martial arts, beginning with Hokushin Shinoh-ryu Iaido during his first year in high school, eventually earning the rank of yon dan (fourth-level black belt). Now known as Grandmaster (Hanshi), Minobu Miki is teaching and creating both international and domestic champions. His San Diego, California dojo has students ranging in age from preschoolers to seniors. The classes include Shito-ryu Karate-do from the heir of the founder of the style, Soke Mabuni Kenzo and Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu Iaido from Meijin Iwata Norikazu. He continues to teach internationally in Asia, Europe and the Americas. He is a Pan American Continent Referee Council Founding member, World Karate Federation (WKF) Technical Committee Chief Delegate of the USA Team and Member of the WKF Referee Council, Chief Referee Council and Pan-American Games Italian Karate Federation, as well as a National Kata Coach, producing two world champions. Tokyo Journal Editor-in-Chief Anthony Al-Jamie spoke with Minobu Miki about his journey to the US and how he got started in the world of karate.

TJ: How did you get started in karate?

HANSHI: When I was growing up in Nagoya, kids never practiced karate. However, everyone was required to participate in some type of martial arts such as judo or kendo. I began my martial arts training in iaido but also participated in kendo. Only when I was in high school did I begin training in karate-do for self-defense since it was more practical.

TJ: You’ve done so many things. What year did you come to the United States?

HANSHI: I came to the States in late 1967 to attend college. I ended up in Tacoma Community College for English. While there, I went to the only dojo in the area. When I was at the Tacoma dojo, Seattle hosted an international tournament. They asked me to compete where I placed second kumite [freestyle fighting]. During that tournament, I met an ex-Marine, Harold Long, who invited me to go to Knoxville, TN. That is how I ended up going to college in Tennessee.

TJ: How was the experience of being Japanese in Tennessee in the ‘70s?

HANSHI: At the state university, there was only one student who was Japanese before me. So, I was completely on my own. The accent there also made the new language even more difficult. So, culturally and linguistically, Tennessee was very challenging. After being in Tennessee for two years, I returned to Seattle where there were at least some Japanese. After four years in Seattle, I then came to San Diego in 1972.

TJ: Do you have any advice for people to defend themselves?

HANSHI: To be realistic, it is more helpful to train mentally instead of trying to physically yell, kick, punch, or grab someone’s throat. You may think that’s a good idea, but often it doesn’t work. If you’re going to take a self-defense class, you need to be prepared psychologically as well. Learn how to avoid dangerous situations, how to help other people and to talk things out. I think these are very important goals for self-defense.

Fumio Demura A Martial Arts Legend Remembered

By Tokyo Journal Editor-in-Chief Anthony Al-Jamie

In the world of martial arts, legends are born, and Fumio Demura was undoubtably one such legend. Demura’s life was a testament to the power of dedication, discipline and the indomitable spirit of a martial artist. Born on September 15, 1938, in Yokohama, Japan, Fumio Demura’s journey through the world of martial arts left an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of practitioners around the globe.

Demura was drawn to the traditional Japanese martial art of Shito- ryu Karate, and it became the foundation upon which he would build his legendary career, achieving the rank of 10th dan in 2022. His determination was evident as he achieved his black belt at the remarkably young age of 12. Under the tutelage of Taira Shinken, Demura developed a particular interest in kobudo and the use of weaponry, such as nunchaku, in 1959, while he was pursuing his bachelor’s degree in economics at Nihon University in Tokyo.

In the early 1960s, Fumio Demura journeyed to the United States. He initially arrived in the U.S. as a temporary visitor, but he soon realized the potential of sharing his martial arts expertise with a new audience. In 1965, Demura made the pivotal decision to stay in the U.S., making it his home, and began teaching karate.

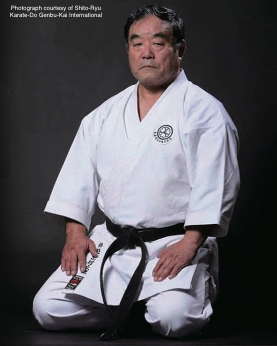

According to Demura, after he published his 1971 book, Nunchaku: Karate Weapon of Self Defense, Bruce Lee would often call him up to discuss nunchaku with questions about the weapon. In addition to teaching at his dojo, Demura gave karate demonstrations at the Japanese Village & Deer Park in Buena Park, California for many years. He shared his knowledge and experiences through books like Karate: The Art of Empty-Hand Fighting and Advanced Nunchaku. He served as a martial arts instructor for such martial arts greats as Chuck Norris and Steven Seagal, he graced the cover of Black Belt Magazine nine times, received the magazine’s Lifetime Achievement Award, was inducted into the publication’s Hall of Fame twice, and earned a place in the Martial Arts History Museum Hall of Fame in 1999. Demura received certificates of recognition from Japanese Cabinet officials for his contributions to the art of karate and earned the All-Japan Karate Federation President’s Trophy for exceptional tournament play. In 1972, he captained the U.S.-Japan Goodwill Championships and served as a member of the national technical committee of the Amateur Athletic Union. He served as president and chief instructor of Shito-Ryu Karate-Do Genbu- Kai International and chairman of the Japan Karate Federation International.

One of the most unique aspects of Fumio Demura’s career was his role as a martial arts actor, technical advisor and stunt double in the television and film industry. He was a key figure in popularizing martial arts in Hollywood and bringing authenticity to martial arts portrayals on the silver screen. He worked alongside some of the greatest names in Hollywood, appearing in such films as Rising Sun, The Island of Dr. Moreau, Mortal Combat and The Karate Kid series. His work on The Karate Kid series left a profound impact on the perception of martial arts in mainstream American culture. Not only was Demura the martial arts stunt double for actor Pat Morita in the first, third, and fourth Karate Kid films, but he was one of the inspirations for the character Mr. Miyagi, becoming the subject of the 2015 documentary The Real Miyagi.

The impact of Fumio Demura’s life and work cannot be overstated. His dedication to karate and martial arts as a whole helped bridge cultural divides and foster understanding among people from different backgrounds. He was a true cultural ambassador, demonstrating the universality of martial arts and the values they represent.

Sadly, on April 24, 2023, the world lost a martial arts legend when Fumio Demura passed away in Santa Ana, California, at the age of 84. However, his contributions to the world of martial arts and the positive impact he had on the lives of his students, as well as those he touched through his work in the film industry, will be remembered forever.

tjThe complete article can be found in Issue #282 of the Tokyo Journal.